Manual 04 for MD++

Vacancy Formation Energy by Energy Minimization

Keonwook Kang and Wei Cai

Contents |

Creating a Vacancy in a Perfect Crystal

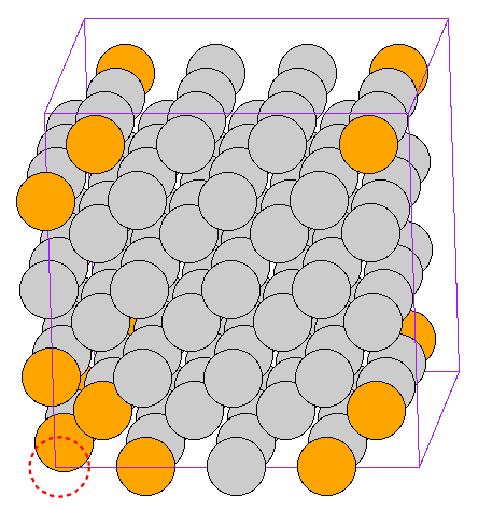

A vacancy is a common point defect in solids. It is an empty site (i.e. a missing atom) in an otherwise prefect crystal structure. Here we discuss how to introduce a vacancy in a perfect crystal using MD++ and how to compute the vacancy formation energy. For more information, see supplementary document: Vacancy formation energy by MD++ . Consider the following MD++ input file, movacancy.script, that creates a vacancy in a perfect BCC Molybdenum crystal.

# -*-shell-script-*-

setnolog

setoverwrite

dirname = runs/movacancy # specify run directory

#--------------------------------------------

# Read in potential file

potfile = ~/Codes/MD++/potentials/mo_pot readpot

#--------------------------------------------

#Create Perfect Lattice Configuration

crystalstructure = body-centered-cubic latticeconst = 3.1472 #(A)

latticesize = [ 1 0 0 5

0 1 0 5

0 0 1 5]

makecrystal finalcnfile = perf.cn writecn

eval # evaluate the potential of perfect crystal

#--------------------------------------------

# Create Vacancy

input = [ 1 # number of atoms to be fixed

0] # index of an atom to be fixed

fixatoms_by_ID # fix a set of atoms by their indices

removefixedatoms # remove fixed atoms

finalcnfile = movac.cn writecn

eval # evaluate the vacancy-formed crystal

#---------------------------------------------

# Plot Configuration

atomradius = 1.0 bondradius = 0.3 bondlength = 0

atomcolor = blue highlightcolor = purple backgroundcolor = gray

bondcolor = red fixatomcolor = yellow

plotfreq = 10 win_width = 600 win_height = 600

plot_atom_info = 3

color00 = "orange" color01 = "purple" color02 = "green"

color03 = "magenta" color04 = "cyan" color05 = "purple"

color06 = "gray80" color07 = "white"

plot_color_windows = [ 2 # number of color windows

-10 -6.8 6 # color06 = gray80

-6.7 -6.0 0 # color00 = orange

]

rotateangles = [ 0 0 0 1 ]

openwin alloccolors rotate saverot plot

sleep quit

We can run this script file by typing

$ bin/fs gpp scripts/movacancy.script

First, MD++ creates a 5×5×5 perfect cubic crystal of BCC Mo with edges along <100> directions. Then it fixes atom 0 by

input = [ 1 # number of atoms to be fixed

0 ] # index of an atom to be fixed

fixatoms_by_ID

and then removs this atom by the command removefixedatoms. The first number in the input array specifies the number of atoms to be removed. For example, if you would like to remove two atoms, say 3 and 8, you can do so by

input = [ 2 # number of atoms to be fixed

3 8 ] # index of atoms to be fixed

fixatoms_by_ID # fix a set of atoms by their index

removefixedatoms # remove fixed atoms

Sometimes, you may want to remove a specific atom you see in the graphic window. You can obtain the index of this atom by clicking the atom with your mouse. Depending on the setting of plot_atom_info, other information is also displayed when you click on the atom. If plot_atom_info = 1, the atom index number and its scaled coordinates are printed when the atom is clicked. If plot_atom_info = 2, the atom index and its real coordinate (in Å) will be printed. If plot_atom_info = 3, the atom index and its local energy (in eV) will be printed.

The script file also sets up two color windows (plot_color_windows) to display the atoms. Atoms with local energy between -10 eV and -6.8 eV are shown in gray and the atoms whose energies lie between -6.7 eV and -6.0 eV are shown in orange. This will highlight the atoms near the vacancy because they usually have a higher local energy. Click the atoms and you will see the actual local energy of these atoms. If you compare the potential energy of the perfect structure and the vacancy-formed structure, you will know which structure has higher energy.

Q.1 If a single atom, whose index is other than 0, is removed from the same perfect structure, do we expect the system to have a different potential energy?

Relaxation

When an atom is removed from a crystal, we expect the neighboring atoms to adjust its positions, e.g. to move toward the vacant site, in order to lower the potential energy. The relaxed structure can be obtained by an energy minimization algorithm, such as the conjugate gradient (CG) method. This can be done by the following lines.

#--------------------------------------------- # Conjugate-Gradient relaxation conj_ftol = 1e-7 # tolerance on the residual gradient conj_fevalmax = 1000 # max. number of iterations conj_fixbox = 1 # fix the simulation box relax # CG relaxation command finalcnfile = relaxed.cn writecn eval # evaluate relaxed structure

Let’s copy the above script and paste it to the movacancy.script right before the last command, sleep quit. You will see that the potential energy of the simulated system keeps decreasing while the relaxation goes on. The potential energy printed by the second eval should be lower than that printed by the first eval.

There are several variables controlling the CG relaxation. conj_ftol is the

tolerance of the residual gradient and conj_fevalmax is the maximum number

of calls to the potential function (effectively limiting the number of iterations).

If conj_fixbox = 1, the shape and volume of simulation cell box is fixed and

only the scaled coordinates of the atoms can change during the relaxation.

If conj fixbox = 0, then all 9 components of the  are allowed to change.

Sometimes, we want to fix some components of the

are allowed to change.

Sometimes, we want to fix some components of the  matrix while allowing

other components to vary. This can be done by specifying the conj_fixboxvec

matrix. For example, if

matrix while allowing

other components to vary. This can be done by specifying the conj_fixboxvec

matrix. For example, if

conj_fixbox = 0

conj_fixboxvec = [ 0 1 1

1 0 1

1 1 0 ]

then only the diagonal components of the box matrix  are allowed to relax.

(The corresponding entries in conj_fixboxvec are zero).

are allowed to relax.

(The corresponding entries in conj_fixboxvec are zero).

Vacancy Formation Energy

The vacancy formation energy Ev is the energy increase that is needed to create a vacancy in a perfect crystal. It can be used to predict the vacancy concentration at thermal equilibrium through

| [n] = exp( − Ev / kBT). |

This is an approximation because we have ignored the vibration entropy contribution Sv of the vacancy. The exact expression is

| [n] = exp( − Fv / kBT). |

where Fv = Ev − TSv is the vacancy formation free energy. These expressions are similar to Boltzmann’s distribution and will be derived in the Appendix.

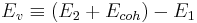

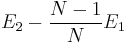

Let E1 be the energy of the perfect crystal with N atoms, and E2 be the relaxed potential energy of the (N − 1)-atom system (containing the vacancy). The vacancy formation energy is not simply the difference between the two, i.e.

, ,

|

because the two systems does not have the same number of atoms.

we need to make sure we compare two systems of the same number of atoms.

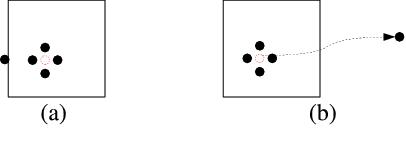

Besides, in a real crystal, no atom is destroyed when a vacancy forms. Instead, when a

vacancy forms in a real crystal, the missing atom moves to the external surface of the

crystal (or to grain boundaries). (See Fig.2(a).) Because we have a very small crystal

in our simulation, subjected to the periodic boundary condition, there

is no external surface. Therefore, we need to account for this effect in a different

way. In the perfect crystal, all atoms contributes equally to the total energy.

Hence, we expect the energy contribution of (N − 1) atoms in the perfect

crystal structure to be  (even though we cannot construct a perfect crystal with (N − 1) atoms in a periodic simulation cell). The vacancy formation energy

Ev can be computed from

(even though we cannot construct a perfect crystal with (N − 1) atoms in a periodic simulation cell). The vacancy formation energy

Ev can be computed from

. .

|

The cohesive energy of the perfect crystal, Ecoh = E1 / N , is the potential energy per atom. Hence the vacancy formation energy can also be expressed as,

|

or

. .

|

The result for BCC Mo using the FS potential is Ev = 2.550 eV<ref>This is consistent with the more accurate tight-binding (TB) model which predicts Ev = 2.46 eV from the reference, M. J. Mehl and D. A. Papaconstantopoulos, “Applications of a tight-binding total-energy method for transition and noble metals: Elastic constants, vacancies, and surfaces of monatomic metals”, Physical Review B 54 4519-4530 1996</ref> which leads to [n] ≈ 1.43 × 10−13 at T = 1000K (kB = 8.621 × 10−5 eV/K).

Q.2 Can you tell the different physical meanings between two expressions

and E2 − E1? You can use Fig. 2 for your explanation.

and E2 − E1? You can use Fig. 2 for your explanation.

Q.3 Recompute Ev with larger and smaller simulation boxes. How does Ev depend on the number of atoms in the simulation cell?

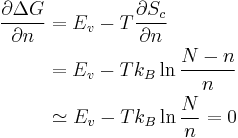

Equilibrium Vacancy Concentration

Here we derive the equilibrium vacancy concentration, Eq. (2), given the formation energy of a single vacancy. Consider a crystal with N sites, n of which are occupied by vacancies. We can write the Gibbs free energy of the solid as

| G = G0 + nEv − TSc. |

where G0 is the free energy of the perfect crystal (n = 0).

Here we have ignored the interaction between the vacancies. This approximation is valid if  .

Sc is the configurational entropy due to the fact that there are Ω different ways

to arrange the n vacancies on N sites.

.

Sc is the configurational entropy due to the fact that there are Ω different ways

to arrange the n vacancies on N sites.

![\begin{align} S_c &= k_B \ln \Omega = k_B \ln \frac{N!}{(N-n)!n!} \\

&= k_B [N\ln N - (N-n)\ln (N-n) - n\ln n ] \end{align}](/mediawiki/images/math/7/a/0/7a036b68597e3215812b8e4ed06bcb9b.png) . .

|

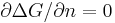

In the last step we have used Stirling’s approximation. At equilibrium, the

Gibbs free energy G reaches minimum, which means  .

.

. .

|

![\therefore [n] \equiv \frac{n}{N} = \exp (-\frac{E_v}{k_B T})](/mediawiki/images/math/2/4/f/24fbcf8595844990ce13efc067eb5310.png)

|

![\mathbf{c}_1 = 4[100], \mathbf{c}_2 = 4[010]](/mediawiki/images/math/d/d/8/dd8cf326fb5894cfaaf9274fb57df2b4.png) , and

, and ![\mathbf{c}_3 = 4[001]](/mediawiki/images/math/c/1/7/c174c99414c63e3ac2abb586273d1a85.png) are the periodicity vectors. The red dotted circle designates the missing atom and the atoms around the vacant site are shown in different color due to their relatively high energy than the others.

are the periodicity vectors. The red dotted circle designates the missing atom and the atoms around the vacant site are shown in different color due to their relatively high energy than the others.